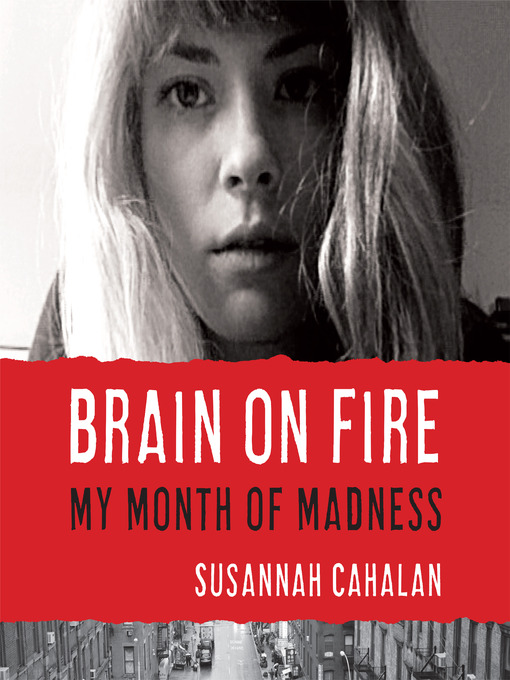

Brain on Fire (2012) is a memoir by New York Post writer Susannah Cahalan that details her struggle with a rare autoimmune disease, anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis. Cahalan recollects the journey through illness that took her from a normal, 24-year-old journalist to a misdiagnosed psychotic patient, and back again. Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness Chapter 20 Summary & Analysis LitCharts. Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness Introduction + Context. Susannah explains to the reader that Dad begins keeping a personal journal to track Susannah's developments and help himself cope. From this journal, Susannah recounts Dad's description of taking the.

Netflix's newest original film might be the most terrifying it's ever made, and it's not even a horror movie. Brain on Fire is a medical mystery drama starring Chlöe Grace Moretz, and it's about the very real and extremely rare disorder that struck journalist Susannah Cahalan when she was just 24. The illness depicted on the film is truly the stuff nightmares are made of, but Cahalan made it through and is alive today. So where is the real Susannah from Brain on Fire now, and is she still feeling the effects of her horrific ordeal?

When Cahalan was struck by her illness in 2009, she was one year into her job as a New York Post reporter. Today, nearly a decade later, Cahalan still lives in New York and still works for the Post, having published her most recent article for the paper on June 16, writing about her experience of seeing a harrowing time in her life turned into a movie. But she wasn't just returning to the paper to address her past; she's been consistently writing articles for the Post for years. Just a week earlier, she wrote a piece on Maine lobsters, and her author page on the Post's website shows scores of articles she's written. It's great to see that Cahalan's ordeal didn't end up adversely affecting her career, but it very well could have.

Cahalan suffered from an incredibly rare anti-immune disorder known as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. The disease most commonly affects women in their childbearing years, like Cahalan, and is four times more likely to occur in women than in men, according to the Anti-NMDA Foundation. The illness is caused when a person's antibodies, which are produced by the immune system to fight infections, begin attacking the NMDA receptors in the brain. These receptors are responsible for much of the brain's activity, including memory, cognitive function, perception of reality, and even autonomic functions like breathing. It's unknown why these NMDA attacking antibodies are produced, but if left untreated, the disease is fatal. If caught early, however, the condition is highly treatable, which explains why Cahalan is perfectly healthy today.

As for the symptoms experienced by Cahalan, they're quite terrifying, and she can't even remember most of what happened to her due to the nature of her illness. It began with relatively minor symptoms: sensitivity to light and numbness on the left side of her body. Then she broke down crying for no reason at work, and began to worry that something was wrong, according to her own 2009 recounting of the episode in the Post. After seeing a doctor and getting no answers, she had a seizure, which prompted more doctor visits. She then became paranoid and delusional, believing her doctors were conspiring against her and that people on TV were talking about her. She stopped eating, stopped sleeping, and had hallucinations, including believing that her father murdered her stepmother, according to the Post. After being admitted to a hospital, she tried to escape and assaulted her nurses.

After a number of false diagnoses, including that she was bipolar or suffering from alcohol withdrawal, Cahalan finally received the correct diagnosis from Dr. Souhel Najjar. He asked her to draw a clock on a piece of paper, and when she did, she put all 12 of the numbers on the right side of the clock face, leaving the left side blank, according to NPR. This informed Najjar that the right side of her brain was inflamed, since it controls the left side of the body. He described the condition as her brain being on fire, which Cahalan later used as the title for her memoir about the ordeal that she published in 2012, Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness.

Start studying Brain on Fire - Susannah Cahalan. Learn vocabulary, terms, and more with flashcards, games, and other study tools. Painstakingly, Susannah draws a clock with all the numbers on the right side, which indicates that the right side of her brain is inflamed.

Today, Cahalan is healthy, though somewhat haunted by what happened to her. She can be considered one of the lucky ones, though. According to the Post, Najjar estimates that 90 percent of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis cases go undiagnosed, meaning those patients will ultimately be killed by their bodies attacking their own brains. It's a horrifying way to go, but thankfully for Cahalan, she lived to help spread the word about this terrifying disorder so more people can hopefully receive treatment in time.

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of 'Brain On Fire' by Susannah Cahalan. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Brain On Fire Real Girl

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What is Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness about? How did Susannah Cahalan put together what happened to her?

Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness tells the story of Susannah Cahalan’s missing month in the hospital. She appeared to have a psychosis, but her brain was attacking itself.

See what happened in Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness.

What Happened in Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness

After twenty-eight days in the hospital, Susannah is discharged. She’ll need an at-home nurse; biweekly visits to the hospital to flush out the antibodies with a plasma exchange; a full-body 3-D scan; and full-time rehab.

Still vastly divorced from her old self, Susannah has little self-awareness when she’s released from the hospital. She makes significant progress over the next few months, but in her own mind, she’s uncertain about herself. For Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness, she had to research herself.

Experts are called in to do an assessment. It reveals a divide between Susannah’s internal world and the world around her. Social situations are especially difficult because she’s aware of how strange she appears to the people around her. Susannah often feels that her true self is trying to connect with the world outside but can’t break past her body. She worries that she’s become boring—the most difficult adjustment to a new self she has to make.

Susannah’s old self finally reawakens. She begins reading again and starts keeping a diary. This was the start of Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness. Her father encourages her to draw upon her memory, but she can recall only numbness, sleepiness, and three seizures. She remembers nothing from her time in the hospital.

As a result of her illness, Susannah has gained 50 pounds. She obsesses about being fat. Her worries about being fat are actually worries about who she will become: Will she remain as slow as she is now, or will she regain the spark that defines her true nature? When people ask, “How are you?” Susannah recognizes that she no longer knows who “I” is.

Susannah regains former functions and personality traits. She summarizes her experience for Paul, her mentor at the Post, and he certifies that her writing skills have returned.

Paul’s encouragement is all Susannah needs. She begins a program of research and becomes obsessed with understanding how a human body attacks itself. Paul actively encourages Susannah to return to work. On the appointed day, Susannah dresses up and takes a train into the city, but both she and Paul realize it’s too soon for her to return to work.

Two weeks later Susannah gets an assignment from the Post. Her article is published on July 28. She’s published hundreds of pieces before, but none have meant more than this one. Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness signals her redemption.

A month later—seven months after her illness forced her to leave work—Susannah returns to her job at the Post. Human Resources advises her tostart off slowly, but she jumps in as if she never left. Unable to type as quickly as before, she records her interviews, her speech slow, plodding. Sometimes she slurs her words. Her coworkers discreetly edit her work, reeducating her in the basics of journalism. Susannah is convinced she’s back to normal, but in fact, she still has a long way to go before she returns to her former self.

Working on Brain on Fire by Susannah Cahalan

That afternoon, the Post’s Sunday editor asks Susannah if she’d be willing to write a first-person account of her illness. It’s the assignment Susannah has been hoping for.

She has four days to write Brain on Fire by Susannah Cahalan. She interviews Stephen, her family, and Drs. Najjar and Dalmau. She learns many things in the course of her research:

- Children make up 40 percent of those diagnosed with the disease.

- Many adults diagnosed with the disease were originally diagnosed with schizophrenia or autism.

- It’s cost-prohibitive to test all psychiatric patients for an autoimmune disease.

- Many doctors don’t keep abreast of current medical research.

The Post’s photo editor wants to illustrate Susannah’s article with images from the EEG videos taken during her stay in the hospital. Watching the videos, Susannah is frightened by seeing herself so unhinged, but she’s more frightened by the fact that emotions that once wracked her so completely have vanished entirely. The Susannah in the EEG video is a foreign entity to the Susannah writing about her own illness.

On October 4, Brain on Fire by Susannah Cahalan runs in the Post. She receives hundreds of emails from people who have the disease and want to know more about it. She even receives phone calls from people who want a diagnosis from Susannah herself. In a few months, Susannah feels comfortable in her own skin again.

Same But Different

Nevertheless, when Susannah compares pictures of herself taken before and after her illness, she notices that something has changed. In her everyday life, she notes subtle differences that indicate she’ll never be the same person she was before.

Sometimes memories from her month of oblivion rush back to her, knocking her off balance. With each memory recovered, she wonders what others remain, knowing there are thousands she’ll never retrieve. The other Susannah, the mad Susannah, calls out to her, saying, “Don’t forget me. Please.”

At one time, Susannah couldn’t answer yes to the question, “Would you take it all back if you could?” Today, she doesn’t regret her month of madness. Its darkness yielded too much light.

Besides writing Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness, Susannah has shared her stories with universities, hospitals, and psychiatric institutions. She helped start the Autoimmune Encephalitis Alliance, a nonprofit foundation fostering research and awareness of the illness.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Susannah Cahalan's 'Brain On Fire' at Shortform.

Susannah Brain On Fire Movie

Here's what you'll find in our full Brain On Fire summary:

Susannah Cahalan Brain On Fire Netflix

- How a high-functioning reporter became virtually disabled within a matter of weeks

- How the author Cahalan recovered through a lengthy process and pieced together what happened to her

- How Cahalan's sickness reveals the many failures of the US healthcare system